State¶

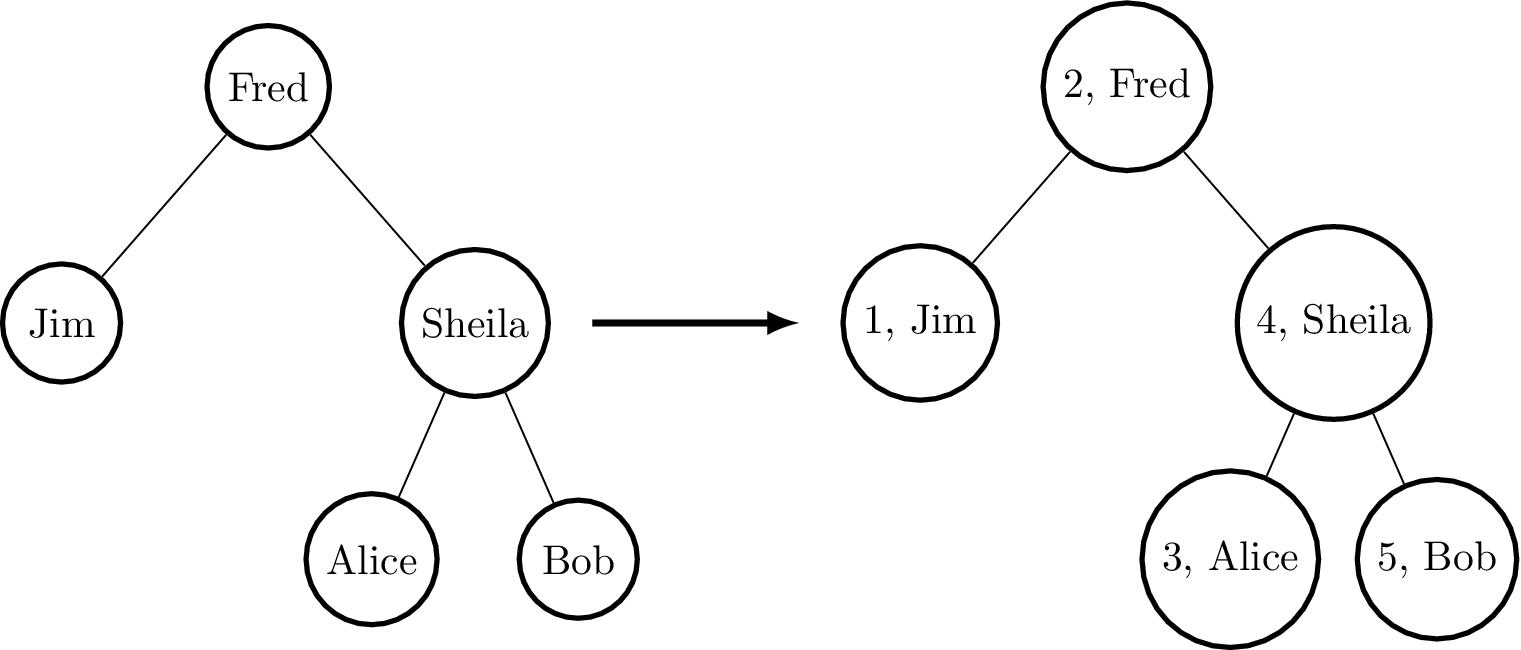

Many programs, even pure programs, can benefit from locally mutable state. For example, consider a program which tags binary tree nodes with a counter, by an inorder traversal (i.e. counting depth first, left to right). This would perform something like the following:

We can describe binary trees with the following data type BTree

and testTree to represent the example input above:

data BTree a = Leaf

| Node (BTree a) a (BTree a)

testTree : BTree String

testTree = Node (Node Leaf "Jim" Leaf)

"Fred"

(Node (Node Leaf "Alice" Leaf)

"Sheila"

(Node Leaf "Bob" Leaf))

Then our function to implement tagging, beginning to tag with a

specific value i, has the following type:

treeTag : (i : Int) -> BTree a -> BTree (Int, a)

First attempt¶

Naïvely, we can implement treeTag by implementing a helper

function which propagates a counter, returning the result of the count

for each subtree:

treeTagAux : (i : Int) -> BTree a -> (Int, BTree (Int, a))

treeTagAux i Leaf = (i, Leaf)

treeTagAux i (Node l x r)

= let (i', l') = treeTagAux i l in

let x' = (i', x) in

let (i'', r') = treeTagAux (i' + 1) r in

(i'', Node l' x' r')

treeTag : (i : Int) -> BTree a -> BTree (Int, a)

treeTag i x = snd (treeTagAux i x)

This gives the expected result when run at the REPL prompt:

*TreeTag> treeTag 1 testTree

Node (Node Leaf (1, "Jim") Leaf)

(2, "Fred")

(Node (Node Leaf (3, "Alice") Leaf)

(4, "Sheila")

(Node Leaf (5, "Bob") Leaf)) : BTree (Int, String)

This works as required, but there are several problems when we try to

scale this to larger programs. It is error prone, because we need to

ensure that state is propagated correctly to the recursive calls (i.e.

passing the appropriate i or i’). It is hard to read, because

the functional details are obscured by the state propagation. Perhaps

most importantly, there is a common programming pattern here which

should be abstracted but instead has been implemented by hand. There

is local mutable state (the counter) which we have had to make

explicit.

Introducing Effects¶

Idris provides a library, Effects [3], which captures this

pattern and many others involving effectful computation [1]. An

effectful program f has a type of the following form:

f : (x1 : a1) -> (x2 : a2) -> ... -> Eff t effs

That is, the return type gives the effects that f supports

(effs, of type List EFFECT) and the type the computation

returns t. So, our treeTagAux helper could be written with the

following type:

treeTagAux : BTree a -> Eff (BTree (Int, a)) [STATE Int]

That is, treeTagAux has access to an integer state, because the

list of available effects includes STATE Int. STATE is

declared as follows in the module Effect.State (that is, we must

import Effect.State to be able to use it):

STATE : Type -> EFFECT

It is an effect parameterised by a type (by convention, we write

effects in all capitals). The treeTagAux function is an effectful

program which builds a new tree tagged with Ints, and is

implemented as follows:

treeTagAux Leaf = pure Leaf

treeTagAux (Node l x r)

= do l' <- treeTagAux l

i <- get

put (i + 1)

r' <- treeTagAux r

pure (Node l' (i, x) r')

There are several remarks to be made about this implementation.

Essentially, it hides the state, which can be accessed using get

and updated using put, but it introduces several new features.

Specifically, it uses do-notation, binding variables with <-,

and a pure function. There is much to be said about these

features, but for our purposes, it suffices to know the following:

doblocks allow effectful operations to be sequenced.x <- ebinds the result of an effectful operationeto a- variable

x. For example, in the above code,treeTagAux lis an effectful operation returningBTree (Int, a), sol’has typeBTree (Int, a).

pure eturns a pure valueeinto the result of an effectful- operation.

The get and put functions read and write a state t,

assuming that the STATE t effect is available. They have the

following types, polymorphic in the state t they manage:

get : Eff t [STATE t]

put : t -> Eff () [STATE t]

A program in Eff can call any other function in Eff provided

that the calling function supports at least the effects required by

the called function. In this case, it is valid for treeTagAux to

call both get and put because all three functions support the

STATE Int effect.

Programs in Eff are run in some underlying computation context,

using the run or runPure function. Using runPure, which

runs an effectful program in the identity context, we can write the

treeTag function as follows, using put to initialise the

state:

treeTag : (i : Int) -> BTree a -> BTree (Int, a)

treeTag i x = runPure (do put i

treeTagAux x)

We could also run the program in an impure context such as IO,

without changing the definition of treeTagAux, by using run

instead of runPure:

treeTagAux : BTree a -> Eff (BTree (Int, a)) [STATE Int]

...

treeTag : (i : Int) -> BTree a -> IO (BTree (Int, a))

treeTag i x = run (do put i

treeTagAux x)

Note that the definition of treeTagAux is exactly as before. For

reference, this complete program (including a main to run it) is

shown in Listing [introprog].

module Main

import Effects

import Effect.State

data BTree a = Leaf

| Node (BTree a) a (BTree a)

Show a => Show (BTree a) where

show Leaf = "[]"

show (Node l x r) = "[" ++ show l ++ " "

++ show x ++ " "

++ show r ++ "]"

testTree : BTree String

testTree = Node (Node Leaf "Jim" Leaf)

"Fred"

(Node (Node Leaf "Alice" Leaf)

"Sheila"

(Node Leaf "Bob" Leaf))

treeTagAux : BTree a -> Eff (BTree (Int, a)) [STATE Int]

treeTagAux Leaf = pure Leaf

treeTagAux (Node l x r) = do l' <- treeTagAux l

i <- get

put (i + 1)

r' <- treeTagAux r

pure (Node l' (i, x) r')

treeTag : (i : Int) -> BTree a -> BTree (Int, a)

treeTag i x = runPure (do put i; treeTagAux x)

main : IO ()

main = print (treeTag 1 testTree)

Effects and Resources¶

Each effect is associated with a resource, which is initialised

before an effectful program can be run. For example, in the case of

STATE Int the corresponding resource is the integer state itself.

The types of runPure and run show this (slightly simplified

here for illustrative purposes):

runPure : {env : Env id xs} -> Eff a xs -> a

run : Applicative m => {env : Env m xs} -> Eff a xs -> m a

The env argument is implicit, and initialised automatically where

possible using default values given by implementations of the following

interface:

interface Default a where

default : a

Implementations of Default are defined for all primitive types, and many

library types such as List, Vect, Maybe, pairs, etc.

However, where no default value exists for a resource type (for

example, you may want a STATE type for which there is no

Default implementation) the resource environment can be given explicitly

using one of the following functions:

runPureInit : Env id xs -> Eff a xs -> a

runInit : Applicative m => Env m xs -> Eff a xs -> m a

To be well-typed, the environment must contain resources corresponding

exactly to the effects in xs. For example, we could also have

implemented treeTag by initialising the state as follows:

treeTag : (i : Int) -> BTree a -> BTree (Int, a)

treeTag i x = runPureInit [i] (treeTagAux x)

Labelled Effects¶

What if we have more than one state, especially more than one state of

the same type? How would get and put know which state they

should be referring to? For example, how could we extend the tree

tagging example such that it additionally counts the number of leaves

in the tree? One possibility would be to change the state so that it

captured both of these values, e.g.:

treeTagAux : BTree a -> Eff (BTree (Int, a)) [STATE (Int, Int)]

Doing this, however, ties the two states together throughout (as well as not indicating which integer is which). It would be nice to be able to call effectful programs which guaranteed only to access one of the states, for example. In a larger application, this becomes particularly important.

The library therefore allows effects in general to be labelled so that they can be referred to explicitly by a particular name. This allows multiple effects of the same type to be included. We can count leaves and update the tag separately, by labelling them as follows:

treeTagAux : BTree a -> Eff (BTree (Int, a))

['Tag ::: STATE Int,

'Leaves ::: STATE Int]

The ::: operator allows an arbitrary label to be given to an

effect. This label can be any type—it is simply used to identify an

effect uniquely. Here, we have used a symbol type. In general

’name introduces a new symbol, the only purpose of which is to

disambiguate values [2].

When an effect is labelled, its operations are also labelled using the

:- operator. In this way, we can say explicitly which state we

mean when using get and put. The tree tagging program which

also counts leaves can be written as follows:

treeTagAux Leaf = do

'Leaves :- update (+1)

pure Leaf

treeTagAux (Node l x r) = do

l' <- treeTagAux l

i <- 'Tag :- get

'Tag :- put (i + 1)

r' <- treeTagAux r

pure (Node l' (i, x) r')

The update function here is a combination of get and put,

applying a function to the current state.

update : (x -> x) -> Eff () [STATE x]

Finally, our top level treeTag function now returns a pair of the

number of leaves, and the new tree. Resources for labelled effects are

initialised using the := operator (reminiscent of assignment in an

imperative language):

treeTag : (i : Int) -> BTree a -> (Int, BTree (Int, a))

treeTag i x = runPureInit ['Tag := i, 'Leaves := 0]

(do x' <- treeTagAux x

leaves <- 'Leaves :- get

pure (leaves, x'))

To summarise, we have:

:::to convert an effect to a labelled effect.:-to convert an effectful operation to a labelled effectful operation.:=to initialise a resource for a labelled effect.

Or, more formally with their types (slightly simplified to account only for the situation where available effects are not updated):

(:::) : lbl -> EFFECT -> EFFECT

(:-) : (l : lbl) -> Eff a [x] -> Eff a [l ::: x]

(:=) : (l : lbl) -> res -> LRes l res

Here, LRes is simply the resource type associated with a labelled

effect. Note that labels are polymorphic in the label type lbl.

Hence, a label can be anything—a string, an integer, a type, etc.

!-notation¶

In many cases, using do-notation can make programs unnecessarily

verbose, particularly in cases where the value bound is used once,

immediately. The following program returns the length of the

String stored in the state, for example:

stateLength : Eff Nat [STATE String]

stateLength = do x <- get

pure (length x)

This seems unnecessarily verbose, and it would be nice to program in a

more direct style in these cases. provides !-notation to help with

this. The above program can be written instead as:

stateLength : Eff Nat [STATE String]

stateLength = pure (length !get)

The notation !expr means that the expression expr should be

evaluated and then implicitly bound. Conceptually, we can think of

! as being a prefix function with the following type:

(!) : Eff a xs -> a

Note, however, that it is not really a function, merely syntax! In

practice, a subexpression !expr will lift expr as high as

possible within its current scope, bind it to a fresh name x, and

replace !expr with x. Expressions are lifted depth first, left

to right. In practice, !-notation allows us to program in a more

direct style, while still giving a notational clue as to which

expressions are effectful.

For example, the expression:

let y = 42 in f !(g !(print y) !x)

is lifted to:

let y = 42 in do y' <- print y

x' <- x

g' <- g y' x'

f g'

The Type Eff¶

Underneath, Eff is an overloaded function which translates to an

underlying type EffM:

EffM : (m : Type -> Type) -> (t : Type)

-> (List EFFECT)

-> (t -> List EFFECT) -> Type

This is more general than the types we have been writing so far. It is

parameterised over an underlying computation context m, a

result type t as we have already seen, as well as a List EFFECT and a

function type t -> List EFFECT.

These additional parameters are the list of input effects, and a list of output effects, computed from the result of an effectful operation. That is: running an effectful program can change the set of effects available! This is a particularly powerful idea, and we will see its consequences in more detail later. Some examples of operations which can change the set of available effects are:

- Updating a state containing a dependent type (for example adding an element to a vector).

- Opening a file for reading is an effect, but whether the file really is open afterwards depends on whether the file was successfully opened.

- Closing a file means that reading from the file should no longer be possible.

While powerful, this can make uses of the EffM type hard to read.

Therefore the library provides an overloaded function Eff

There are the following three versions:

SimpleEff.Eff : (t : Type) -> (input_effs : List EFFECT) -> Type

TransEff.Eff : (t : Type) -> (input_effs : List EFFECT) ->

(output_effs : List EFFECT) -> Type

DepEff.Eff : (t : Type) -> (input_effs : List EFFECT) ->

(output_effs_fn : x -> List EFFECT) -> Type

So far, we have used only the first version, SimpleEff.Eff, which

is defined as follows:

Eff : (x : Type) -> (es : List EFFECT) -> Type

Eff x es = {m : Type -> Type} -> EffM m x es (\v => es)

i.e. the set of effects remains the same on output. This suffices for

the STATE example we have seen so far, and for many useful

side-effecting programs. We could also have written treeTagAux

with the expanded type:

treeTagAux : BTree a ->

EffM m (BTree (Int, a)) [STATE Int] (\x => [STATE Int])

Later, we will see programs which update effects:

Eff a xs xs'

which is expanded to

EffM m a xs (\_ => xs')

i.e. the set of effects is updated to xs’ (think of a transition

in a state machine). There is, for example, a version of put which

updates the type of the state:

putM : y -> Eff () [STATE x] [STATE y]

Also, we have:

Eff t xs (\res => xs')

which is expanded to

EffM m t xs (\res => xs')

i.e. the set of effects is updated according to the result of the

operation res, of type t.

Parameterising EffM over an underlying computation context allows us

to write effectful programs which are specific to one context, and in some

cases to write programs which extend the list of effects available using

the new function, though this is beyond the scope of this tutorial.

| [1] | The earlier paper [3] describes the essential implementation details, although the library presented there is an earlier version which is less powerful than that presented in this tutorial. |

| [2] | In practice, ’name simply introduces a new empty type |

| [3] | (1, 2) Edwin Brady. 2013. Programming and reasoning with algebraic effects and dependent types. SIGPLAN Not. 48, 9 (September 2013), 133-144. DOI=10.1145/2544174.2500581 http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2544174.2500581 |